Figure 17-1. The BlindSurfer label.

The U.S. is not the only country that has an accessible web design law. This chapter takes a look at web accessibility efforts around the world and highlights those countries that have adopted and implemented an accessible web design policy or law.

Many countries have adopted the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 or a variation, along with rules particular to that jurisdiction. Some countries, such as Australia and Denmark, have also adopted the U.S. Section 508 web requirements. Many quality marks or labels certifying accessibility are also covered in this chapter; including a project of the European Union (EU) Web Accessibility Benchmarking (WAB) Cluster to recommend a uniform quality mark for all countries implementing certain accessible web design criteria in the EU.

If you are a web developer, manager, information technology (IT) professional, IT lawyer, or decision maker, you should be aware of the legal requirements affecting websites. Consult this chapter if you are entering into a contract to provide web development services within any of these countries. Although legal sanctions are discussed whenever provided under the law— such as civil and even criminal penalties for not designing accessibly— this chapter should not be considered legal advice. Specific legal questions can best be answered by seeking the advice of legal counsel.

As of the writing of this chapter, 25 countries or jurisdictions have web design laws and policies, including Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, and the UK. If your country does not have an accessible web law or policy, perhaps you might use this chapter as leverage to encourage legislation (a suggestion from a web designer in Asia).

After reading about the Maguire v. Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games web accessibility case in Chapter 2, it should not be a surprise to hear that the Internet Industry Association (IIA, Australia' s national Internet industry organization) issued a press release with the headline, "IIA Warns SOGOC: Decision Puts Business on Notice".

As you learned in Chapter 2, the Australia Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) of 1992 requires that all online information and services be accessible (see Section 24 of this Act). According to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), the body charged with ensuring the accessibility of website content under the DDA, the DDA applies to any individual or organization developing a web page in Australia or placing or maintaining a web page on an Australian server. More specifically, the HREOC states

This includes pages developed or maintained for purposes relating to employment; education; provision of services including professional services, banking, insurance or financial services, entertainment or recreation, telecommunications services, public transport services, or government services; sale or rental of real estate, sport; activities of voluntary associations; or administration of Commonwealth laws or programs.

World Wide Web Access: Disability Discrimination Act Advisory Notes

Therefore, all Australian web developers should be familiar with the HREOC document titled World Wide Access: Disability Discrimination Act Advisory Notes. Although this document does not have direct legal force, the Advisory Notes indicate that agencies can consider them when dealing with inaccessible website complaints. HREOC also commented that implementing the Advisory Notes "make[s] it far less likely that an individual or organization would be subject to complaints about the accessibility of their web page.

"

Of interest are the following Advisory Notes comments on the Portable Document Format (PDF):

The Portable Document Format (PDF) file system developed by Adobe has become widely used for making documents available on web pages. Despite considerable work done by Adobe, PDF remains a relatively inaccessible format to people who are blind or vision-impaired. Software exists to provide some access to the text of some PDF documents, but for a PDF document to be accessible to this software, it must be prepared in accordance with the guidelines that Adobe has developed. Even when these guidelines are followed, the resulting document will only be accessible to those people who have the required software and the skills to use it. The Commission' s view is that organisations who distribute content only in PDF format, and who do not also make this content available in another format such as RTF, HTML, or plain text, are liable for complaints under the DDA. Where an alternative file format is provided, care should be taken to ensure that it is the same version of the content as the PDF version, and that it is downloadable by the user as a single document, just as the PDF version is downloaded as a single file.

The Advisory Notes also contain a warning on the use of Macromedia Flash in Section 2.4, "Access to New and Emerging Technologies":

[W]ork is currently underway to make Macromedia' s Flash technology accessible to people who use screen-reading software. While some positive progress has been made, it will be a considerable time before most users will benefit, and even then, Flash may be accessible only in certain specific circumstances. It is certainly wrong for web designers to assume that improvements in the accessibility of a technology mean that it can be used indiscriminately without regard for the principles of accessible web design.

On June 30, 2000, the Online Council issued a press release announcing the adoption of the W3C WCAG as the minimum website access standards by all Australian governments (see www.dcita.gov.au/Article/0,,0_4-2_4008-4_15092,00.html).

The Guide to Minimum Website Standards was designed to assist Australian Government departments and agencies to implement the Government' s minimum website standards. Originally published in 2000, the guide was updated in April 2003.

For additional resources on Australian website policies for the States of Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia, see the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) Policies Page.

If you are developing a website for a bank, be sure to follow the Australian Bankers' Association Industry Standard, which, was developed with the cooperation of the HREOC. You will find this standard includes W3C WCAG technical specifications in addition to U.S. Section 508 requirements.

If you are developing a website for a member of the Australian Interactive Multimedia Industry Association (AIMIA), you need to know that the IIA and the AIMIA have jointly developed an Accessibility Web Action Plan. This is the industry' s first plan for encouraging web accessibility awareness and helping members to develop and maintain accessible websites. As with other action plans developed under the DDA, this plan has no copyright or commercial confidentiality restrictions. However, adoption or attribution to IIA/AIMIA requires permission from the Taskforce Chair. The plan includes key performance indicators to ensure that it is regularly evaluated and effective.

Web accessibility legislation under the E-Government Act was voted by the Austrian Parliament in February 2004 and entered into force on March 1, 2004. The Act serves as the legal basis for the instruments used to provide a system of e-government and for closer cooperation among all authorities providing e-government services. According to the November 26, 2004, official report, titled The Information Society in Austria:

Programmes for challenged persons: Websites of public authorities must be made accessible to everybody regardless of any physical or technical obstacles. Barrierfree websites can be set up in accordance with the so-called "

Web Accessibility Initiative" (WAI)-guidelines. By 1 January 2008 all websites of public authorities must be set up to comply with the needs of challenged persons.

For the English text of the E-Government Act addressing accessible websites, take a look at Part I: Paragraph 3. For the German version of the E-Government Act, see www.parlament.gv.at/pls/portal/docs/page/PG/DE/XXII/BNR/BNR_00149/fname_014980.pdf.

Although Belgium has no federal legislation that specifically requires accessible websites, the obligation to develop accessible websites is being interpreted as a requirement based on the Anti-Discrimination law of 2003. The legislation was voted on February 25, 2003, and published in the Official Journal on March 17, 2003.

According to the EU Information Society portal on policies in Belgium, one of the main clauses of the Anti-Discrimination law is that "[a]ny lack of reasonable adjustments for people with disabilities will be considered as a form of discrimination.

" The Dutch-adapted version of W3C WCAG is posted at the portal site.

Since 2000, the Belgium BlindSurfer Project has received the support of public entities and has established an accessibility label that enables a website visitor with visual disabilities to know that the website has met an adapted version of W3C WCAG requirements. The label is now distributed by two Belgium organizations: Blindenzorg Licht en Liefde and Oeuvre Nationale des Aveugles. According to Marc Walraven (Project Manager of ASCii's Web Accessibility and Usability Department), the BlindSurfer label has been proposed as the official quality mark for accessible websites. BlindSurfer is a member of the EuroAccessibility Consortium, which is committed to work with the Guidelines and Techniques developed by the WAI. See the January 2005 presentation entitled "E-Accessibility Initiatives Undertaken in Belgium and on the Demand of European Institutions in the Field of E-Accessibility."

Here is the BlindSurfer accessibility screening process:

A candidate Website sends its screening application to the BlindSurfer evaluation team via a special screening application form. The site URL is then provided to at least two experts, a blind person and a person with good vision who will screen the site. The site is then examined on the basis of a thirteen-point checklist in order to determine if it meets the accessibility conditions. This list is based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) published by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) that is part of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). These directives are acknowledged as a world standard and have been accepted by many public authorities. The evaluation results are then collected and a screening protocol is written. This protocol contains, if necessary, a certain number of explanatory comments in order to facilitate finding solutions for possible remaining accessibility problems. If the screening is positive, the site owner is awarded the BlindSurfer label. If the site is not perfectly accessible, the BlindSurfer team is ready to provide any available information and suggestions for realizing the needed adaptation works. Websites that receive the BlindSurfer label are asked to respect the usage conditions of the label of which we remind the most important ones:

- in principle, the label must be located on the site homepage

- the label must be present with its indissociable

alt-tag complement which contains the "BlindSurfer" text- the label must include a hyperlink towards our BlindSurfer site

- the label may not be modified

As the label owner, BlindSurfer reserves itself the right to withdraw the label from a site that, owing to a transformation, would not meet the accessibility directives any more. This is why checks are performed from time to time.

Figure 17-1 shows the BlindSurfer label.

Figure 17-1. The BlindSurfer label.

In a June 11, 2004, plan called TOEWEB (an abbreviation of Toegankelijke Websites

, which means Accessible Websites

), the Flemish Government decided that websites and related online services of its institutions—

including Flemish Parliament, the Flemish Government, the Ministry of the Flemish community, and the Flemish public institutions—

should be made accessible. Target dates were for the Internet websites to be accessible by the end of 2007 and intranet websites by 2010.

According to the plan, websites and any related online services should be made accessible to people with disabilities and the elderly within a reasonable time frame and within the available budgets. It anticipated that the first results would be visible before June 30, 2005, for websites that could easily be made accessible. Priority is given to websites and services related to employment, welfare, and mobility, and those explicitly addressing people with disabilities and the elderly.

Before the end of 2005, each webmaster was to provide a clear Action Plan for the period 2006–2010 to the Flemish Parliament. These Action Plans were to include clear indications on timing, budgetary impact, and a proposal for long-term quality assurance measures. See www2.vlaanderen.be/ned/sites/toegankelijkweb/ (in Dutch) for more information.

In June 2001, the Walloon Government set up and adopted the Wall-On-Line Project (in French) to establish a multiple-purpose and accessible online portal for all local services. Oeuvre Nationale des Aveugles is responsible for the technical aspects, and a list of priority sites was established and made available online in 2004. These sites were expected to be made accessible by the end of 2005.

According to Marc Walraven, on February 20, 2003, the Walloon Region in Belgium decided to actively start addressing the problems of the region' s inaccessible websites. On April 10, 2003, measures were adopted to improve the accessibility of the majority of public websites.

In Brazil, the Law on Accessibility (L. 10.098) enacted in 2000 requires accessibility in communication and barrier removal and expressly guarantees the right of persons with disabilities to information and communication. In 2004, Decree 5.296 provided more detailed provisions for implementation and requires all governmental Internet websites to be accessible to persons with disabilities (see https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil/_ato2004-2006/2004/decreto/d5296.htm for the Portuguese version). This decree provides that all governmental websites— local, state, and federal— are to be accessible within 12 months and that a symbol indicating Internet accessibility will be posted on those sites that are accessible to people with disabilities. As of the writing of this chapter, I was not able to verify the extent of compliance with this decree. (Many thanks to Mary Barros-Bailey for the English translation.)

According to the International Disability Rights Monitor Project Americans 2004 Report, the Brazilian Technical Standards Association (ABNT) has created a working team for the development of a technical standard on accessibility to Internet content. However, technical standards were not available at the time this chapter was written.

In May 2000, the government of Canada adopted a policy for all federal government organizations that requires conformance to W3C WCAG Priority 1 and 2 Checkpoints. In September 2005, the Common Look and Feel Standards and Guidelines for the Internet (CLFI) was updated. According to the Secretary of the Treasury Board, it enables institutions to be confident that Canadians can use websites and that website design is in "full accord with Government of Canada legislation and policies.

" English and French versions of the CLFI are available at www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/clf-nsi/default.asp.

Instead of creating policy, the Province of Ontario moved forward to adopt legislation in 2005 that is broad in scope and includes the requirement that both public institutions and private businesses provide accessible websites. Effective June 14, 2005, the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) established the Accessibility Standards Advisory Council for developing proposed standards that must be implemented within five years. This rule-making process requires the Council to submit developed standards to the Minister, who will make the standards public for receiving comments. After considering the public comments, the Council may make any changes and will then provide the Minister with the proposed accessibility standard. The Minister will decide within 90 days whether or not to recommend the proposed standards for adoption by regulation. Once the standard has been adopted as a regulation, all affected persons and organizations will be required to comply within the timelines set out in the standard. In addition, organizations will be required to file accessibility reports to confirm compliance. Spot audits will verify the reports, and there are tough penalties for noncompliance.

Jutta Treviranus, expert witness for the Maguire v. Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games case, was appointed to the Advisory Council on December 13, 2005. According to an e-mail communication I received from Ms. Treviranus, she is serving on the Information, Communications and Technology standards committee and will be covering web accessibility standards (WCAG, ATAG, and UAAG). At the time this chapter was written, the committee had not made an accessible web design standard recommendation. You can follow the progress of this effort at the web page of the Accessibility Directorate of Ontario.

Although there is no national law in Denmark requiring web accessibility, there are guidelines about accessibility for government agencies. The Interoperability Framework includes accessible web design standards and serves as a guideline for public agencies as they develop information technology plans and projects. It contains descriptions and recommendations of selected standards, technologies, and protocols for implementation of e-government in Denmark. Both W3C WCAG and the U.S. Electronic and Information Technology Accessibility Standards (Section 508) are incorporated into the guideline.

Seeking to ensure that the knowledge society will be more accessible to all, the National IT and Telecom Agency has established the Competence Center IT for All (KIA). KIA was established according to the action plan Disability No Obstacle, published by the Minister for Science Technology and Innovation in January 2003.

KIA participates in the eAccessibility expert group, which is providing advice to the eEurope Advisory Group in the area of eInclusion as part of the eEurope 2005 Action Plan. This Action Plan seeks to ensure a true and universal information society involving all social groups. For more information, follow the English link at www.oio.dk/.

KIA has launched the Public Procurement Toolkit in order to make it easy for public authorities to include accessibility requirements in public procurement, as well as in the development and purchase of digital solutions. A web-based tool, the Public Procurement Toolkit contains a large database of functional accessibility requirements. It offers concrete specifications on how to make accessible solutions, guidance on why the authorities must provide accessible solutions, and a review of the challenges caused by inaccessible solutions. Four guidelines form the core of the Toolkit:

For each guideline, two documents provide technical specifications and guidance. The technical document supporting an accessible website contains a list of the technical specifications needed to design accessibly. The specifications include the U.S. Section 508 and W3C WCAG. The guidance document provides information on the benefits of accessible solutions and the obstacles that inaccessible websites cause. This document explains the levels in the specifications and guidance on the problems each specification solves. It is here that users of the Toolkit can read why they should include a specification and what would be the effect if it is not included.

The Toolkit is designed for the public procurement process with the specifications identified so they can be easily placed in the Calls for Tender or Request for Proposals. For more information see www.oio.dk/it_for_alle/udbudsvaerktoejskassen and www.braillenet.org/colloques/policies/documents/Shermer.doc.

As early as 1994, the EU has recognized the importance of web accessibility through various action projects.

In December 1999, the eEurope— an Information Society for All initiative was launched by the European Commission to bring the benefits of the Information Society to all Europeans.

In June 2000, the Feira European Council adopted the eEurope Action Plan 2002, which included steps to address access to the Web for people with disabilities.

The September 2001 communication from the Commission to the Council, The European Parliament, The Economic and Social Committee, and The Committee of Regions, "eEurope 2002: Accessibility of Public Web Sites and their Content," emphasized that

Public sector web sites and their content in Member States and in the European institutions must be designed to be accessible to ensure that citizens with disabilities can access information and take full advantage of the potential for e-government.

http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/com/cnc/2001/com2001_0529en01.pdf, page 7

On February 27, 2002, a press release announced that the European Economic and Social Committee (ESC) had welcomed the Commission's communication on the accessibility of public websites and their content, as referenced in the preceding paragraph. According to the press release,

The ESC also took the opportunity to rebut some misunderstandings relating to the time and cost involved in making public web sites compatible with the needs of disabled and elderly people. '

In many Member States the objection has been raised that the process of implementation of the WAI (web accessibility initiative) guidelines will constitute an excessive financial engagement. This assumption is simply wrong, because implementing the accessibility guidelines from the first is only a little more expensive than not implementing them,' says the opinion, which suggests that national funding be earmarked for implementation of the communication's provisions.

Also according to the press release, the ESC indicated that work was needed to make the new version of their website, Europa II, accessible in time for the 2003 European Year of Disabled People. For the entire report on the accessibility of websites, see Opinion CES-189(2002) published on February 20, 2002.

On June 13, 2002, the European Parliament adopted a resolution to support the importance of web accessibility in EU institutions and Member States. The resolution states that the W3C WCAG 1.0 (Priority 1 and 2 levels) and future versions should be implemented on public websites. In addition, it called from all EU Institutions and Member States to also comply with the W3C Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines by the year 2003. See EP (2002) 0325 and following the links English > Parliament > Access to Documents > Register of Documents > Search

, and entering "eEurope 2002 Accessibility.

"

The eEurope 2005 Action Plan continues to monitor the progress of accessibility for the EU public sector websites.

Promoting an inclusive society is one of the primary policies of the EU effort, as seen in the June 1, 2005, European Commission launch of i2010: European Information Society 2010. The objective of i2010 is to boost the digital economy by fostering growth and jobs and to promote an inclusive society.

On September 15, 2005, the European Commission issued an eAccessibility Communication calling for more coordinated action to ensure the accessibility of information and communication technologies accessible to all citizens. According to the press release,

- While continuing to support ongoing measures such as standardisation, Design for All (DFA), Web accessibility and Research & Technology Development, the Commission proposes the use of three policy levers available to Member States:

- to improve the consistency of accessibility requirements in public procurement contracts in the ICT domain,

- to explore the possible benefits of certification schemes for accessible products and services.

- to make better use of the "

e-Accessibility potential" of existing legislationhttp://europa.eu.int/information_society/policy/accessibility/policy/com-ea-2005/index_en.htmm.

As for the Europa server, the European Commission has adopted level A (Priority 1) of the W3C WCAG 1.0 for conforming new and updated websites. The Europa web accessibility policy web page states that although some top-level Europa sites already meet level A, the European Commission is continuing to move forward to achieve conforming for the existing pages. For the pages that conform to WCAG 1.0, the WAI conformance logo is being utilized. See http://europa.eu/geninfo/accessibility_policy_en.htm for more information.

The Web Accessibility Benchmarking (WAB) Cluster is a cluster of European projects to develop a harmonized European methodology for evaluation and benchmarking of websites. More than 20 partners are working together on an assessment methodology based on W3C WAI that will support the expected migration from WCAG 1.0 to WCAG 2.0. The first draft of the Unified Web Evaluation Methodology (UWEMO.5) is online.

Other WAB Cluster projects include the development of a quality mark or website label for accessibility, as well as the development of test suites for evaluation tools and integration of testing modules in content management systems.

The W3C WCAG 1.0 has been adopted as part of the Finnish Government Public Administration Recommendations in the JHS 129 Guidelines for Designing Web Services in the Public Administration, Ministry of the Interior, December 2000. According to the JHS English abstract, the recommendation provides public authorities with guidance on how to plan, implement, and purchase online services. It describes the process for producing online services and implementing a user interface designed especially for end users that addresses usability and accessibility. The recommendation also includes application guidelines for online services with regard to the use of metadata as described in the JHS 143 recommendation. For more information, see www.jhs-suositukset.fi/ (follow the In English > Search:

links and enter "JHS recommendation abstracts

").

As early as 1993, the Nordic Guidelines for Computer Accessibility provided guidance on the design of accessible information and communication technologies, including websites. It was updated in 1998 by the Nordic Cooperation on Disability, an organization under the Nordic Council of Ministers composed of the governments of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden.

Production: The following text includes the character (as in Law n°) 2005-102, article 47

On February 11, 2005, French legislation was published requiring all web services of the public sector to conform to the international guidelines for web accessibility. W3C WCAG is indirectly referenced in Law n° 2005-102, article 47, providing for "equal rights and opportunities, participation and citizenship of people with disabilities.

" Web services of the public sector have a deadline of three years to become accessible. Sanctions for noncompliance will be defined in the Code of Practice of the law.

According to the EU Information Society report on web accessibility in France, the Ministry of People with Disabilities drafted the law, and guidelines for implementation were prepared by the e-Administration ADAE (Agence pour le Développement de l' Administration Electronique). The ADAE web accessibility guidelines are based on the AccessiWeb criteria developed by the BrailleNet Association and include usability criteria based on the work of Jacob Nielsen. The Code of Practice of the law will define the web accessibility rules as set forth in the ADAE guide.

Although the BrailleNet Association has developed the AccessiWeb label (bronze, silver, or gold), shown in Figure 17-2, and provides evaluation and certification of websites, as of the writing of this chapter, public websites are not legally required to submit to the BrailleNet Association AccessiWeb evaluation. See the report at http://europa.eu.int/information_society/policy/accessibility/z-techserv-web/wa_france/index_en.htm.

Figure 17-2. The AccessiWeb label.

Previously, the Prime Minister published standards for accessibility of public websites on October 12, 1999, administrative guidelines (circulaire): the Mission pour les Technologies de l'Information et de la Communication (MTIC). This action sought to promote documentation and tools for public sector webmasters, and these were available on MTIC's website formerly at www.atica.pm.gouv.fr/interop/accessibilite/l (no longer available):

On April 27, 2002, the German legislature passed the Act on Equal Opportunities for Disabled Persons. Subsequently, at the federal level, the Ordinance on Barrier-Free Information Technology was established July 24, 2002. This ordinance is referred to as BITV.

According to the EU Information Society report on web accessibility in Germany, the BITV is based on W3C WCAG 1.0 with the following changes:

WCAG Priorities A and AA are integrated into Priority I of the German BITV;

WCAG Priority AAA corresponds to Priority II of the German BITV; and

Checkpoint 2.2 of WCAG 1.0 which already had 2 priorities assigned has now been divided into checkpoints 2.2 (color contrast in images) and 2.3 (added- color contrast for text) of the German BITV

In addition, the report states that the federal BITV

Applies to All Federal Administration authority websites and pages including their publicly accessible websites and pages and IT based graphic user interfaces that are publicly accessible;

Applies to All private web-pages of private companies covered under the BITV;

Directs that private companies have the obligation to begin negotiations with registered organizations for people with disabilities to produce "

targeted agreements" for implementing accessible web; andProvides that only the obligation for negotiation is mandatory whether or not an agreement is reached.

In his presentation "E-Accessibility in Germany: Act and Ordinances, Outcome of Benchmarking and Activities," dated January 31, 2005, Rainer Wallbruch points out that the BITV annex contains requirements and checkpoints that incorporate WCAG 1.0 as much as possible. He points out that "every public internet page has to reach WAI conformance level AA and in addition to this, every public central navigation page should reach WAI conformance level AAA

" (see www.braillenet.org/colloques/policies/wallbruch_paper.html).

As for sanctions, although no precedent has been set, the BITV gives registered organizations for people with disabilities the right to take legal actions on behalf of people with disabilities who experience discrimination by federal information technology that is not compliant.

The EU Information Society report also discusses web accessibility efforts at the State level. References to WCAG for web accessibility are not uniform because some States adopt the federal BITV and others adopt different subsets and definitions. For a review of the various State efforts on accessible web, see the link identified in the report at www.wob11.de/gesetze/landesgleichstellungsgesetz.html (German only).

Currently, various organizations and private companies provide a range of quality labels based on BITV. The German standardization authority, DIN-CERTCO, is working on developing a national label, as well as several national certification centers.

The Hong Kong government has established internal web accessibility guidelines for both Internet and intranet web pages, entitled Guidelines on Dissemination of Information through Government Homepages. The guidelines are based on the W3C WCAG 1.0 as well as input from the industry and organizations such as the Hong Kong Blind Union.

As early as 1999, the Hong Kong government began to revise all government websites according to web accessibility guidelines. This revision was accomplished in early 2003 according to the E-Government Roadmap Report.

The Digital 21 Strategy website includes tips on accessibility as well as web accessibility education and training in Hong Kong since 2001.

For further information, see the WebAim collection of links posted at www.webaim.org/coordination/law/hongkong.

According to the National Disability Authority (NDA), Irish public policy includes requirements for government department websites to conform to Priority Levels 1 and 2 of the W3C WCAG 1.0 (see www.accessit.nda.ie/policy_and_legislation.html).

On October 5, 2005, the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, officially launched the Excellence through Accessibility Award program. This program, developed by the NDA in partnership with the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, acknowledges departments and agencies that have made their services more accessible. Through this award, NDA seeks to support the achievement of maximum accessibility of all public services for people with disabilities in Ireland. For more information, see www.nda.ie/cntmgmtnew.nsf/accessibilityHomePage?OpenPage.

In June 2002, the NDA issued the Irish National Disability Authority IT Accessibility Guidelines for web, telecommunications, public access terminals, and application software. The guidelines for web accessibility adopt W3C WCAG 1.0.

In addition, recent legislation in Disability Act 2005 requires access to information and provides for a complaint-filing process effective December 31, 2005. Section 28 of the legislation states in part

Where a public body communicates in electronic form with one or more persons, the head of the body shall ensure, that as far as practicable, that the contents of the communication are accessible to persons with a visual impairment to whom adaptive technology is available.

Companies who have received directly or indirectly loans or funding from the government also fall under the definition of "public body.

"

The NDA is charged with the development of codes for practice for Disability Act 2005, and the October 4, 2005, Code of Practice draft points to the accessible web requirements of the NDA IT Accessibility Guidelines as well as Level AA conformance with the W3C WCAG 1.0. It is interesting that in a footnote within the draft Code of Practice, the NDA noted that the Department of the Taoiseach'

s "New Connections—

A Strategy to realize the potential of the Information Society" stated that "all public websites are required to be WAI (level 2) compliant by end of 2001" (see www.nda.ie/ and follow the links Standards > Code of Practice > Draft Code of Practice on Accessibility of Public Services and Information provided by Public Bodies

).

This summary of the current state of accessible web laws and policies in Italy is based on the unofficial English translation provided by the Information Systems Accessibility Office at CNIPA (National Organism for ICT in the Public Administration) accessed in January 2006 at www.pubbliaccesso.gov.it/english/index.htm. Refer to this site for English links to the law and regulations discussed here. (Many thanks to Dr. Patrizia Bertini, Senior E-Accessibility Advisor and Researcher of the European Internet Accessibility Observatory, for her assistance.)

On January 9, 2004, national legislation was enacted by Law 4, setting in motion provisions to support access to information technologies for people with disabilities and the accessible design of public websites. The law applies to public administrations, private firms that are licensees of public services, regional municipal companies, information and communication technologies (ICT) services contractors, public assistance and rehabilitation agencies, and transport and telecommunication companies where the State has a prevalent interest. Article 11 of Law 4 directed that the following steps be established through a decree by the Minister for Innovation and Technologies:

Guidelines for the different accessibility levels and technical requirements; and

Technical methodologies for verifying the accessibility of Web sites as well as assisted evaluation programs that can be used for this purpose.

Subsequently, the Decree of the President of the Republic, March 1, 2005, No. 75, provided the implementation regulations, and the Ministerial Decree of July 8, 2005, provided the technical methodologies and evaluation programs that became effective August 2005. The Ministerial Decree of July 8, 2005, contains the following:

The scope of the accessibility effort in Law 4 is broad, and it also provides a benchmark for public administrations in the following areas:

The Digital Administration Code was adopted as a Legislative Decree on March 7, 2005, and provides the legal framework for the development of e-government and the removal of "virtual barriers.

" It came into force on January 1, 2006, and requires all government websites to be accessible within two years. The law is available in Italian at www.padigitale.it/home/testodecreto.html.

The Italian technical requirements take into account the following sources:

gov.it domain (www.pubbliaccesso.gov.it/normative/circolare_aipa_20010906.htm, in Italian)According to Article 9 of Law 4, failure to comply with the provisions of the law implies both executive responsibility and disciplinary action, and can also include possible criminal prosecution and civil liability.

The scheme for certifying website accessibility includes both a technical evaluation performed by experts using a variety of techniques and a subjective evaluation conducted by end users, including users with disabilities. The evaluation is to be carried out independently of the government by assessors that will register on a list held by the CNIPA for private sector operators. Evaluators are expected to be announced in the coming months. Should the evaluation validate accessibility, then the private sector operators can request the accessibility logo for their website from the Department of Innovation and Technologies. The CNIPA will verify whether websites and services continue to meet accessibility requirements.

Regarding the accessibility logo, the following is an extract of Annex E of the Italian Ministerial Decree of July 8, 2005:

Annex E

Accessibility logo for Internet technology-based web sites and applications

1. Logo without asterisks

This consists of the sienna-coloured outline of a personal computer, together with three stylised human forms which, from the left, are sky-blue, blue and red respectively, coming out of the screen with open raised [arms]. This logo corresponds to level one accessibility, associated with conformity with the requirements laid down for the technical assessment.

2. Logo with asterisks

This consists of the same design described above, with the addition of asterisks. This guarantees conformity with the requirements of the technical assessment and the next level of quality achieved by the site, following a positive outcome of the subjective assessment, in accordance with the provisions of Annex B(1). This level of quality is indicated by one, two or three asterisks in the part of the logo showing the keyboard of the personal computer. In particular:

a) Logo with one asterisk in the part showing the keyboard:

corresponds to the level of accessibility certifying that the technical assessment has been passed and that, on conclusion of the subjective assessment, an average overall value greater than 2 and less than 3 has been attributed.

b) Logo with two asterisks in the part showing the keyboard:

corresponds to the level of accessibility certifying that the technical assessment has been passed and that, on conclusion of the subjective assessment, an average overall value greater than or equal to 3 and less than 4 has been attributed.

c) Logo with three asterisks in the part showing the keyboard:

corresponds to the level of accessibility certifying that the technical assessment has been passed and that, on conclusion of the subjective assessment, an average overall value greater than or equal to 4 has been attributed.

Japan is a leader in seeking international standardization in the accessibility of technology. In 1998, in response to a proposal from Japan, the Committee on Consumer policy of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) at its general meeting adopted a resolution to set up a task force. The ISO task force was charged with developing a policy statement on general principles and guidelines for the design of products and the environment to address the needs of older persons and persons with disabilities. The working group, led by Japanese members, actively carried out the task and finalized the general principles in early 2002 as the ISO/IEC Guide 71— Guidelines for standards developers to address the needs of older persons and persons with disabilities.

I would like to especially thank Kaoruko M. Nakano, Vice President and Secretary of Pacific, Prologue Corporation of San Jose, California, and Masaya Ando of Allied Brains, Inc., Tokyo, Japan, for providing source documentation and various translations for this section on the accessible web effort in Japan.

In June 2004, the Japanese Standards Association (JSA) established JIS X 8341-3 as an official Japanese industrial standard for web content information accessibility. The standard is based on ISO/IEC Guide 71 (JIS Z 8071)— Guidelines for standards developers to address the needs of older persons and persons with disabilities. In fiscal year 2003, the working group that developed JIS X 8341-3 was dissolved, and a new working group, Web Accessibility International Standards Research Working Group, was launched in fiscal year 2004. The objectives of the new working group are international standard harmonization with W3C WAI WCAG and other guidelines around the world and to promote JIS X 8341-3 in Japan.

According to a 2005 CSUN presentation entitled "Japanese Industrial Standard of Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and International Standard Harmonization" (which I attended), JIS X 8341-3 was developed by taking into consideration W3C WCAG 1.0 and specific Japanese issues. Presenters Takayuki Watanabe, Tatsuo Seki, and Hazime Yamada explained that WCAG 1.0 was not directly adopted because WCAG 1.0 was known to have some drawbacks and that W3C WAI was working on WCAG 2.0. For further information about the concerns discussed at this presentation, see www.csun.edu/cod/conf/2005/proceedings/2162.htm. For a comparison between JIS X 8341-3 and the WCAG, see the CSUN 2004 presentation. The JIS Web Content Guideline can be purchased online at the JSA web store.

Accessible web design efforts appear to have had a positive impact on businesses in Japan. For example, since 2002, Fujitsu Limited has been seeking to improve web accessibility and should be commended for including accessibility as part of brand development. According to Mr. Kosuke Takahashi, Manager, Corporate Brand Office, Fujitsu Limited,

Fujitsu has considered that one of the vital roles of an information technology (IT) company is to popularize its accessibility improvement activities in society and make the fruits of its efforts freely available to the public. This philosophy is based on Fujitsu' s mission of continually creating value and enhancing mutual beneficial relationships within our communities worldwide. Improvement of Web accessibility should not be implemented just by individual companies; instead, it should be achieved through society-wide collaborative activities.

A web accessibility guideline for the removal of information barriers was first announced in May 1999, by the Telecommunication Accessibility Panel. This guideline contained some of the rules from the W3C WCAG. Members of the panel included the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (see The Guidelines to make Web Content Accessible, in Japanese).

The following year brought a report from the same panel recommending that a web accessibility evaluation tool (J-WAS) be developed in order to promote accessible web design. Issued on May, 23, 2000, the report noted that the nature of Japanese language characters as well as the popular use of cell phones for the Web warranted attention to this matter. The report also noted the importance of including the opinions of the elderly and people with disabilities in the system planning (see "The plan to assist the use of the information and communication technology, and secure the web accessibility for elderly and disabled individuals,

" www.soumu.go.jp/joho_tsusin/pressrelease/japanese/tsusin/000523j501.html in Japanese, and www.icdri.org/Asia/japanpress.htm):

According to Masaya Ando of Allied Brains, Inc., one of the accessibility difficulties unique to the Japanese language is mispronunciation by screen readers. For example, one Kanji (the Chinese-based characters of Japanese) can be pronounced in several different ways. It is also difficult to complete a sentence with Kanji that can be understood by everyone. This is because the Japanese language consists of three different kinds of characters— Kanji, Katakana, and Hiragana— and although there is a standard for Kanji used in everyday Japanese life, the individual's comprehension level will vary with age, generation, and education. Moreover, in the Japanese writing system, words are not separated by spacing, and so the screen reader will not pronounce a word correctly when a space exists within the word.

By November 6, 2000, the government declared that websites of all ministries and the national public sector should apply the web accessibility guideline. At this Joint Meeting of the IT Strategy Council and the IT Strategy Headquarters (The Fifth Conference), it was also decided that the web accessibility evaluation tool (J-WAS) should be developed and used by government organizations to increase the accessibility of their web pages after April 2001 (see www.kantei.go.jp/jp/it/goudoukaigi/dai5/5siryou7-1.html, in Japanese).

In addition, November 2000 also brought Japanese legislation impacting IT law entitled Basic Law on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society. Also known as Basic IT Law, Article 8 provided the basis for addressing accessible web design (see www.kantei.go.jp/foreign/it/it_basiclaw/it_basiclaw.html):

Article 8. In forming an advanced information and telecommunications network society, it is necessary to make active efforts to correct gaps in opportunities and skills for use of information and telecommunications technology that are caused by geographical restrictions, age, physical circumstances, and other factors, considering that such gaps may noticeably obstruct the smooth and uninterrupted formation of an advanced information and telecommunications network society. Approved by the Japanese Diet on 29 November 2000, the law became effective 6 January 2001.

The e-Japan Policy program for barrier-free access has resulted in significant policies impacting the accessible web. On March, 29, 2001, the government IT Strategy Headquarters announced a number of policies, such as the following (see VII. Crosscutting Issues, 2. Closing the Digital Divide, subpart 2) Overcoming Age and Physical Constraints):

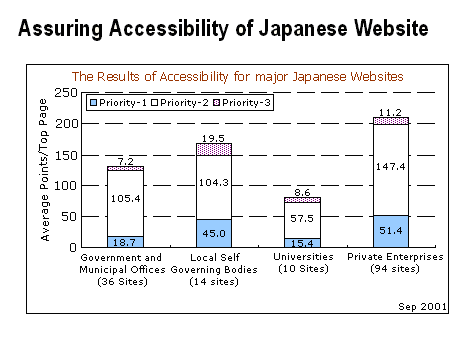

Ongoing work for the development of J-WAS (the web accessibility evaluation tool) continued until it went public on the Web with a trial experiment in September 2001. The September 2001 trial experiment (in Japanese), resulted in the findings shown in Figure 17-3.

Figure 17-3. J-WAS findings (published with permission from Uchida, H., Ando, M., Ohta, K., Shimizu, H., Hayashi, Y., Ichihara, Y.G. & Yamazaki, R.: Research And Improving Web Accessibility in Japan, Slide 7 – "The Results of Accessibility for Major Japanese Web Sites," Internet Imaging III Proceeding of SPIE, Vol. 4672, pp. 46-54, 2002).

Korea has information laws that provide people with disabilities and older adults with the rights to use and access information equally without any assistance. In 2002, Article 7 of Korea' s law on bridging the digital divide was revised to require government, local autonomous bodies, and public organizations to consider establishing policies so that people with disabilities and older adults could use ICT services.

According to information I received from Mr. Ki-Hoon Kim (Manager of the Standards Coordination Team for the Standardization Department of Telecommunications Technology Association), the implementing ordinances recommended that the Minister of Information and Communications (MIC) develop a guideline to encourage accessibility. As a result, in 2002, the MIC established the Guideline for Fostering ICT Accessibility of the Senior and Disabled People. Also in 2002, the agency for technology and standards developed a Korean Industrial Standard entitled Guidelines for standards developers to address the needs of the senior and persons with disabilities based on the ISO/IEC Guideline 71.

As for the Web, in 2004 the Telecommunications Technology Association (TTA), a private ICT standardization organization, established the Web Contents Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 as a TTA standard based on the W3C WCAG. Published on December 23, 2004, the Korean Web Contents Accessibility Guidelines are Standard Number TTAS.OT-10.0003. In 2005, the web standard was adopted as a Korean Information and Communications Standard. TTA is also establishing Korean Authority Tools Accessibility Guidelines and Korean User Agent Accessibility Guidelines based on the W3C standards.

Mr. Ki-Hoon Kim also reported to me that in 2005, the MIC carried out a survey on whether or not public institutions observed web accessibility standards and subsequently distributed the results and recommendations to each public institution so that the institutions could make their websites more accessible. As of the writing of this chapter, the MIC is planning to seek mechanisms for improving web accessibility awareness, including the use of a web accessibility certification system.

Although Luxembourg does not have a national law in force requiring the accessible design of websites, there are mandatory guidelines for all public institutions that create and maintain a website. The official standardization document, Charte de normalization de la presence sur Internet de l' état, was published May 30, 2002, and was approved by the National Commission for Information Society. The following are the main goals of this effort:

Service eLuxembourg (SEL) is tasked to validate websites according to the standardization document prior to the web pages being launched online. SEL is a government service in charge of planning and coordinating e-government in Luxembourg. See the EU Information Society web page for details.

In the Netherlands, under the Act on equal treatment on the grounds of handicap or chronic illness, there is an obligation to produce accessible websites. The Act (Stb. 2003, 206) was published in December 2003 and contains no references to the WCAG.

In 2001, Drempels Weg (literally meaning "away with barriers

") was started as an initiative of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Four national ambassadors took on the task of education and outreach about barriers created by inaccessible websites. In 2002, the National Accessibility Agency took charge of the project. See www.drempelsweg.nl/smartsite.dws?id=51 for more information.

Beginning in 2005, Drempels Weg was replaced by the Quality Mark drempelvrij.nl. This quality mark is based on the WCAG 1.0 Priority 1 checkpoints, as shown in Figures 17-4 and 17-5. Details about the assessment, costs, and user complaint procedure for visitors who believe that a website does not meet the quality mark standards can be found at www.accessibility.nl/toetsing/waarmerkdrempelvrij. An official quality mark register is maintained at www.drempelvrij.nl/waarmerk (in Dutch).

Figure 17-4. Quality mark drempelvrij.nl for meeting all 16 checkpoints.

Figure 17-5. Quality mark drempelvrig.nl for meeting 13 out of 16 checkpoints.

The Bartimeus Accessibility Foundation is the first certified inspection organization. For further information see www.accessibility.nl/ (in Dutch).

New Zealand policy development began in 2000, when the Government Information Systems Manager Forum (GOVIS) started adapting the UK Government' s Web Guidelines to the New Zealand environment. According to the December 2003 Cabinet Paper for Web Guidelines, the UK Guidelines were chosen because they were based on the W3C WCAG 1.0. The New Zealand Government Web Guidelines have undergone a number of revisions. The current version is 2.1.3 as of the writing of this chapter.

The New Zealand Government Web Guidelines specify in Section 6.3.2, that content developers apply the W3C WCAG 1.0 as follows:

Must satisfy priority 1 checkpoints (see exemption below)

Should satisfy priority 2 checkpoints

May satisfy priority 3 checkpoints

An exemption: The WAI requirement to identify changes in natural language with the lang attribute (http://www.w3c.org/TR/WCAG10/#gl-abbreviated-and-foreign) does not extend to the Māori language in these Guidelines, while support for correct rendering in screen readers also does not extend to the Māori language.

The Guidelines also recommend that

Since a number of the priority 2 and 3 checkpoints are not especially onerous to implement, agencies should aim to go beyond the requirements of priority 1 where this can be done economically.

CAB Min (03) 41/2B, dated December 15, 2003, directed all Public Service departments, the New Zealand Police, the New Zealand Defence Force, the Parliamentary Counsel Office, and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service to implement the Guidelines as follows:

All new or revised content produced for existing non-Guideline compliant websites after 1 April 2004 should comply with the Guidelines as closely as possible

Existing websites should become compliant with version 2.1 of the Guidelines on the Next Occasion of a complete website redevelopment occurring before 1 January 2006

All websites must comply with at least version 2.1 of the Guidelines by 1 January 2006

All websites must comply with subsequent versions of the Guidelines produced after 1 January 2006.

For more information, see the Minute of Cabinet decision.

The Cabinet Paper for Web Guidelines points out that the Web Guidelines enable agencies to be in compliance with law and government policy. The Guidelines assist agencies to meet their obligations under the Official Information Act 1992; the Human Rights Act 1993; the Policy Framework for Government-held Information; and the E-government, New Zealand Disability, and Māori Language strategies (see www.e.govt.nz/standards/web-guidelines/cabinet-paper-200402).

More specifically, agencies would fail to meet certain legal obligations if they did not implement the Guidelines. For example, the Official Information Act 1992 requires government to increase the availability of official information and provide each person with proper access to it as part of good government. The Human Rights Act 1993 requires nondiscrimination in access to public places and facilities, including government websites, and in the provision of public goods and services. Noncompliant websites could result in breach of either of these Acts.

If you are involved in the development of web pages in New Zealand, you should also know that the Guidelines in Section 1.8 specifically recommend that the following people read the document:

Section 6.3.3 of the Guidelines addresses web document markup and requires valid HTML 4.01 Transitional. If an agency wishes to adopt XHTML, rather than HTML, the agency must seek an exemption from this requirement from the E-government unit. Section 6.3.3 further states that

Although deprecated tags are part of the HTML 4.01 specification and therefore will not make a web document invalid HTML, you should avoid their use in favour of newer methods of achieving the same thing. The tags deprecated in the HTML 4.01 specification are

<applet>,<basefont>,<center>,<dir>,<font>,<isindex>,<menu>,<s>,<strike>,<u>. You must not use proprietary tags like<layer>and<comment>.

Section 6.3.4 of the Guidelines addresses style sheets and requires that text be properly marked up to signify document semantics (headings, lists, emphasis, and so on), rather than using styles to change appearance alone. In particular, it states

You should use style sheets to define the visual appearance of pages. You should not rely on custom styles to denote document structure. You should use HTML structural tags (

<h1>to<h6>,<ol>,<ul>etc) instead, so that people are not disadvantaged using non-visual browsers or browsers that ignore style sheets. You may use selectors, properties and values that are defined in CSS2, but only where you are sure they will degrade gracefully in browsers that don' t correctly interpret CSS2 or do so poorly.

Section 6.3.5 of the Guidelines addresses scripting and requires websites using scripting to degrade gracefully, so that the site remains fully functional if scripting is ignored. All information and services on a government website must be available whether or not scripting is available to the user. It goes on to say that

You should use scripting languages only where required and ensure text-based alternatives are available. Where active scripting is used, it should conform to the ECMAScript standard, rather than a proprietary standard, and should use the W3C Document Object Model (DOM), which is a platform-and language-neutral interface that will allow programs and scripts to dynamically access and update the content, structure and style of documents.

The Ministry of Government Administration and Reform (formerly the Ministry of Modernisation) has published new web accessibility goals for public websites in Norway. The eNorge 2009: the Digital Leap plan states that by 2007, 80 percent of all official government websites will comply with Norge.no'

s quality criteria on accessibility.

As of the writing of this chapter, the new criteria for the 2007 assessment has not been formulated (according to Mr. Haakon Aspelund of the Directorate for Health and Social Affairs). It is expected that the W3C WAI will be used as a reference in the new guidelines. The Norge.no official government portal quality criteria involve three parts: accessibility, user friendliness, and useful information.

Previously, the ICT strategy for 2004 through 2005 was that public websites must be user friendly and compliant with the W3C WAI international standards. According to Harald Jorgensen, Department of IT Strategy and Statistics for the Norwegian Directorate for Health and Social Affairs, since June 13, 2003, it has been official government policy that public information on the Internet must be compliant with the W3C WAI standards (see www.w3.org/WAI/EO/2004/02/policies_eu.html).

In addition, the Norwegian government has introduced a national quality mark for public websites (see the EU Information Society Report on Norway). Mr. Haakon Aspelund reported to me that Norge.no has made four manual assessments of all public websites in Norway, and the last assessment, which included more than 700 websites, was completed in autumn 2005. The quality mark is star-based, and the assessment information on the accessibility of the websites can viewed by the number of stars (one through six), by the accessibility score, by the average score, and so on (see www.norge.no/kvalitet/kvalitet2005/sok.asp, in Norwegian).

Of interest is the ongoing EU project by the European Internet Accessibility Observatory (EIAO), which is carried out at the Agder University College in Norway. The observatory will consist of a web-crawling robot that is planned to automatically assess approximately 10,000 European websites on a regular basis, storing assessment data in a data warehouse for statistics and information retrieval, and provide a basis for decision making.

For additional background documents about web accessibility efforts in Norway, see the following (all in Norwegian):

Portugal

Portugal was one of the early pioneers in national legislation for accessible web. The Portuguese Special Interest Group (PASIG), a nonprofit, nongovernment organization, established an International Accessibility Board consisting of well-known accessibility experts (I was a member of the Board). Working with PASIG, the Board compiled Internet accessibility guidelines that were submitted to the Portuguese parliament on February 17, 1999. This petition resulted in a national law requiring accessible websites: Accessibility of Public Administration Web Sites for Citizens with Special Needs (Resolution of the Council of Ministers Number 97/99), also referred to as RCM97/99.

Article 1 of this law requires the following entities to implement accessible websites: general directorates and similar agencies, departments, or services, as well as public corporations. This includes universities, schools, and State corporations such as television, radio, and banks.

The accessible web requirement language is broad:

The methods chosen for organizing and presenting the information . . . must permit or facilitate access thereto to all citizens with special needs (art. 1; point 1.1. of RCM97/99) ... The accessibility referred to in article 1.1 above shall apply, as a minimum requirement, to all information relevant to the full understanding of the contents and for the search of same (art. 1; point 1.2) ... To achieve the goals referred to in the previous article, the organizations mentioned therein must prepare both the written contents and the layout of their Internet pages so as to ensure that: a) Reading can be performed without resorting to sight, precision movements, simultaneous actions or pointing devices, namely mouse. b) Information retrieval and searching can be performed via auditory, visual or tactile interfaces. (art 2, of RCM97/99)

In addition, the law requires an accessibility quality mark or label fixed to the homepage to indicate that the website complies with accessibility requirements. (art 3, of RCM97/99).

The Codes of Practice in the Accessibility Requirements provide minimum requirements for accessibility and include a recommendation to conform to the accessibility requirements of W3C WCAG 1.0. They also promote the use of the U.S. National Center for Accessible Media' s Web Access Symbol, shown in Figure 17-6. Websites that have the accessibility label fixed at the homepage are listed at the Accessibility Gallery.

Figure 17-6. NCAM Web Access Symbol.

As for quality monitoring, the law requires that the Minister for Science and Technology monitor and evaluate the enforcement of this act and inform the government regularly on the progress of its application (art 5, of RCM97/99). Two reports have been produced: one in February 2002 and the second in December 2003.

The Knowledge Society Agency (UMIC) accessibility program, called ACESSO, performs evaluations and consultation. The main UMIC portal in English is at www.infosociety.gov.pt/. The UMIC provides resources such as the Portugal' s Best practices guide for the construction of the web sites of the state administration and Guide for software, which addresses issues of concern for the accessibility of products and services (www.umic.gov.pt/UMIC/CentrodeRecursos/Publicacoes/guia_boas_praticas.htm, in Portuguese).

On July 15, 2003, the Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced the launch of a three-year e-Government Action Plan II for 2003–2006. According to the description of the plan, the goal is to "transform the Public Service into a Networked Government that delivers accessible, integrated and value-added e-services to our customers, and helps bring citizens closer together

" (See the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore Factsheet under section E).

According to Mr. Leonard Cheong of the eGov Policies and Programmes Division of the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore, web content accessibility efforts were implemented as a set of guidelines under the Website Interface Standards (WIS) for the Singapore Government on August 18, 2004. His team is responsible for the effort. WIS aims to establish a set of standards and guidelines for Singapore Government websites and online services to meet the following goals:

Singapore Government agencies have been given a three-year grace period to adopt WIS. As for the W3C WCAG, Mr. Cheong reported (in an e-mail exchange with me in February 2006) that agencies were given the flexibility to make the judgment call depending on the needs of the customers they served. A good example is the Senior Citizen Portal under the Family & Community Development category in the eCitizen portal. A visit to the eCitizen portal finds the W3C WCAG 1.0 Level A badge or quality mark on the website.

Further, in following W3C WCAG 1.0, Mr. Cheong explained the process:

The checklist provided by W3C will be referenced by agencies seeking to make the websites WCAG compliant. The process, as recommended by WCAG, is to ensure that the recommendations in the checklist are adhered to before placing the logo on the website. We are aware that a version of WCAG 2.0 is in the midst of development. Our team tracks this closely and will make the necessary recommendations during our policy review once the WCAG 2.0 is officially released.

Spain has four national laws related to accessibility in general:

Law 34 includes an obligation to fulfill generally recognized accessibility criteria and does not mention W3C WCAG. Also referenced as LSSICE, Law 34 specifies that all public administration websites and all websites financed by public funds must be accessible before December 31, 2005. Article 8 provides sanctions that include the removal of the data from the website.

Royal Decree 209 discusses the W3C WCAG guidelines for obtaining Priority Level AA.

For further information about web accessibility efforts in Spain, including the national laws in Spanish, see the EU Information Society report on Spain.

In support of the March 2000 national disability law, the national action plan for disability policy, From patient to citizen (1999/2000:79), requires Swedish government authorities to ensure that their premises, activities, and information are accessible to people with disabilities. Individual action plans, including the implementation of accessible public sector websites, were required to be submitted by December 21, 2001, and to be implemented no later than 2005.

Supporting Guidelines for Websites, Version 2, were published in June 2004 and incorporate material from all WCAG 1.0 checkpoints. For further information about the effort, see the EU Information Society report on Sweden.

At the Tenth Asia Pacific Telecommunity Forum in October 2005, Ms. Wantanee Phantachat, Director of the Assistive Technology Center of the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC), reported on "Thai Developments in Usability and Accessibility".

Published in 2003, A Guideline on ICT Accessibility for Persons with Disabilities sought to promote accessibility of ICT. In 2004, it became the policy of the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology to promote web accessibility in e-government. The action plan calls for all departments in all Ministries— more than 280 organizations— to have their websites conform to the W3C WCAG 1.0. Both the NECTEC and the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology conduct surveys on website development, including web accessibility and usability. In 2004, 2 websites out of the 280 websites were in partial conformance with WCAG 1.0. A second survey in 2004 found that 5 websites were in partial conformance with WCAG 1.0. It is interesting to note that IBM launched its Thai-speaking web browser, Home Page Reader, in 2003.

Although web accessibility is not specifically mentioned in the UK disability rights legislation, it is mentioned in the Code of Practice that provides a guide as to what might or might not be considered unlawful.

Readers should be aware of two primary pieces of legislation:

Effective May 27, 2002, the Code of Practice: Rights of Access to Goods, Facilities, Services and Premises under the DDA specifically references web accessibility:

- Section 2.2 (page 7): The Act makes it unlawful for a service provider to discriminate against a disabled person:

- by refusing to provide (or deliberately not providing) any service which it provides (or is prepared to provide) to members of the public; or

- in the standard of service which it provides to the disabled person or the manner in which it provides it; or

- in the terms on which it provides a service to the disabled person.

- Section 4.7 (page 39): From 1 October 1999, a service provide has had to take reasonable steps to change a practice, policy or procedure which makes it impossible or unreasonably difficult for disabled people to make use of its services;

- Sections 2.13-2.17 (pages 11-13): What services are affected by Part III of the Act [DDA]? An airline company provides a flight reservation and booking service to the public on its website. This is a provision of a service and is subject to the Act;

- Section 5.23 (pages 68-69): For people with hearing disabilities, the range of auxiliary aids or services which it might be reasonable to provide to ensure that services are accessible might include ... accessible websites; and

- Section 5.26 (page 71): For people with visual impairments, the range of auxiliary aids or services which it might be reasonable to provide to ensure that services are accessible might include ... accessible websites.

The e-Government Unit, which is housed within the UK Government Cabinet Office, has posted web accessibility guidelines that "are a comprehensive blueprint of best practices for building and managing well designed, usable and accessible websites

" at www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/e-government/policy_guidance/. In Section 2.4, entitled "Building in universal accessibility + checklist," the guidelines require that UK websites conform to the W3C WCAG 1.0 Priority Level 1 "A" standard.

The Disability Rights Commission (DRC) was established in April 2000 by an Act of Parliament. Part of the DRC' s duties include monitoring the DDA. The DRC has the power to conduct formal investigations, and in 2003, it launched an investigation into UK website accessibility. See the DRC 2004 formal investigation report.

One outcome of the formal investigation has been for the DRC to commission the British Standards Institution (BSI) in April 2005 to produce formal guidance on web accessibility. The guidance to be developed is to be a Publicly Available Specification— PAS 78: Guide to Good Practice in Designing Accessible Websites. According to the DRC, this step is necessary in part because of the knowledge gap of web developers and the prevalence of web-authoring tools that do not make W3C-compliant code. See the DRC press release. See Appendix C of this book for more information about PAS 78.

This chapter introduced the accessible web design policies and laws around the world. You learned that at least 25 countries or jurisdictions implement W3C WCAG 1.0, a combination of W3C WCAG 1.0 and U.S. Section 508 web requirements, or another variation of rules particular to that jurisdiction. In addition, you learned that in some countries, sanctions or penalties are available for noncompliance— with Italy providing for criminal sanctions as well as civil liability. You also learned that a number of website quality marks or labels have been developed for certifying accessibility based on varying criteria.

You now have a core understanding of some of the international issues and practices supporting accessible web design policies and laws. This chapter should serve as a key resource whenever you are contemplating web development work for clients within any of the countries covered by this chapter.